Classroom in One Voice

Classroom in One Voice

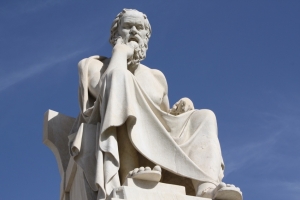

Sophists and Socrates

Dialectic as the standard method of philosophical enquiry probably began with Socrates. He took exception to the methods of the Sophists (from which the word ‘sophisticated’ originates) for engaging in argument. They were a professional group of philosophers that took a fee to teach the skills of rhetoric; the art of the public speaker. What Socrates took exception to was their indifference to truth; they were concerned only with teaching how to win an argument not with which argument was true. Two ancient Geek words capture the distinction between the approach of the Sophists and Socrates respectively: eristic and dialectic. The first of these is ‘combative’ and the second ‘collaborative’.

Plato’s Dialogues

In fact, we only know about Socrates from Plato’s written works in which he depicts the character of Socrates, and most of his philosophical works were written in dialogue form, detailing discussions between Socrates and various other characters from Athens. Although they represent an internal dialogue in the head of Plato, his dialogues are, prima facie, an externalisation of the enquiry process; that is, something going on outside of the heads of the interlocutors and between the different speakers.

Classroom Philosophy and Magnets

When doing philosophy in the classroom it is the Socratic model that we begin with because it is very difficult to get children to engage in a philosophical discussion or thought process on their own. Put a group of children together and they naturally engage in dialectic, pushing the enquiry into directions it could never go with just one child. We use the external process of dialectic to magnetise children into philosophical enquiry. And it works.

Descartes swallowed Plato!

Now take a look at Descartes’ Meditations. This is not written in dialogue form, there is only one speaker addressing the reader who cannot object or question; it looks very different to Plato. But take a closer look and you will see that it is not quite as simple as this. The dialogue is taking place but implicitly. Descartes seems to have swallowed Plato and internalised the process of dialectic. If you read the first Meditiation carefully you will notice that there are different speakers but given only one voice: the narrator’s. Descartes makes a point in on sentence and then raises an objection in the next; he then responds to the objection in the next sentence and the enquiry continues in this fashion. This is what has sometimes been called the dialogue in one voice.

The classroom in one voice

One of the overall aims of the philosophy project in primary school is to internalise the dialectic process so that any one child can learn to question and challenge their own thoughts and assumptions as if they were someone else. This has prodigious implications for self evaluation, moral development and critical thinking. If this is achieved then the child has learned to engage in second-order thinking.

Why philosophy should be taught in primary school

As you can imagine, a process like this, i.e. the internalisation of the dialectic process, needs time to be properly assimilated by a student, and it is best if the habit is formed at an early stage of a child’s development so that it is more easily naturalised (think of language learning). Because of the obvious difficulties of trying to confer this kind of habit to teenagers, it is therefore best to do this before adolescence, so, learning dialectic is best done when in primary school.

Posted by Philosophy Foundation Admin on 9th January 2012 at 12:00am

Category: Philosophy, P4C, Education