In out, in out, shake it all about

The Philosophical Triangle

On The Philosophy Foundation blog recently, we have seen posts by Pete Worley on the Hokey Kokey method, and Steven Campbell-Harris on his Kokey Hokey Method.

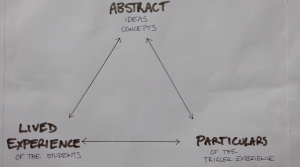

These interesting posts remind me of a diagram I have often drawn on the board when working with teachers who I was training in P4C. I'm not a great one for making up names for techniques, diagrams and the like (I guess I have a lingering suspicion of this from reading de Bono). But I had to call the picture below something, so I have called it a 'foci triangle' (see, I told you I wasn't very good at clever names).

Here's the idea. Both Pete's Hokey Kokey and Steven's Kokey Hokey talk about a two way movement between the more abstract and the more particular. In Pete’s example, the particular is a specific historical event (the Vietnam War) and its associated concrete question Was the ‘domino theory’ a good reason for the Americans to go to war in Vietnam? Although Steven also talks about this abstract-particular movement, he has in mind the particularities of the students' own experience of the world: how they use and understand words.

In my diagram, there is a three way movement: between the abstract ideas/concepts/discussions, the particularities of the specific situation that is the trigger for the discussion (be it a story, dialogue, newspaper article, concrete question, historical event…), and the particularities of the students' own lived experiences.

The first of these three categories is what makes the discussion recognizably philosophical, of course. I guess we have all seen communities of inquiry where the discussion seldom or never visits this realm.

The second category provides a common experience for the community, so that they are all focused together on a common inquiry. This is why Matthew Lipman was so insistent that his stories be read in common around the class. The particular experience embodied in the trigger is often also somewhat neutral - no one student is emotionally invested in it, and so it can provide a non-threatening ground for testing out the abstract ideas.

The third category is where the discussion becomes connected to each student's own understanding of the world. Here, students are constructing understanding through connecting what they know to the new (or, at times, reconstructing the old to fit in with the new). Here, for example, is where the power of anecdotes lies, provided those anecdotes are connected to the first two categories.

For a community of inquiry to get bogged down in any one of these categories has dangers. Being stuck in the abstract risks disengagement and the ‘what’s the use of all this’ question. Concentrating merely on the trigger experience means that the inquiry remains in a disciplinary context: literary critique, psychological conjecture, historical investigation or the like. To remain in the lived experiences of the students involves an endless swapping of anecdotes and stories that lack any purpose beyond hearing the experiences of others.

I have always thought it useful to make this distinction between the two types of particularities, so teachers can pay attention to both, as well as the abstract philosophical realm. The triangle gives teachers a structure for thinking about what interventions or questions in the discussion can help the students to move between the three categories, and thus bind the discussion into a holistic philosophical dialogue that makes a difference to students’ learning and way of operating in the world.

Tim Sprod is author of Discussions in Science and Philosophical Discussions in Moral Education.

Posted by on 29th September 2016 at 12:00am

Category: Philosophy, P4C, Guest Blogger, Education