Pomegranates – a review by Pieter Mostert

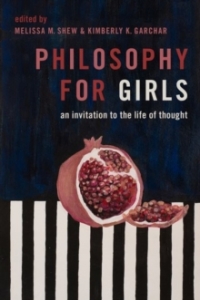

Melissa Shew & Kimberly Garchar (eds.): Philosophy for girls. An invitation to the life of thought. Oxford University Press, 2020, xxvii + 289 p.

It was in the spring of 1971. After a long and cold winter – I spent my gap year in Minnesota – time got tight: I had to decide what to study at university. When I try to recall what made me decide to study philosophy, I immediately think of reading Dostoyevski’s “Crime and Punishment”. That was a convincing book, a book that made me think. Thank you, Fyodor!

“What kind of book <…> do you wish had existed when you were discovering your own questions and growing intellectually?” [p. 1], the editors asked their authors. Twenty chapters are their answers, each on a specific philosophical theme, ranging from pride and courage to technology and art.

The book is not only ‘for girls’, but also by girls and about girls. That’s clear from the cover and it makes the book stand out. Most convincing for me are the chapters that are built around a central character from fiction. In the chapter on self-knowledge, the reader meets Jane Austen’s Emma, in the one on pride it is Emily Bronte’s Jane Eyre, the theme of credibility is explored through the life of Cassandra, and anger is exemplified through Medusa. I find this an attractive and motivating approach: philosophy is not just about ‘thought’, philosophy is a life of thought, as is emphasised in the subtitle. The chapters are written in an inviting and encouraging style and come close to what I would have liked “had existed when you were discovering your own questions”. They encourage the reader to think and maintain a healthy dose of self-confidence. Is there more to wish from an introduction to philosophy? I don’t think so.

Other chapters are built around case studies. The chapter on art is around two painters, Berthe Morisot and Agnes Martin, the one on technology features Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein, or the modern Prometheus”. In a natural flow, the exploration of these cases evolves into an introduction of the more general philosophical questions. I found that quite convincing and helpful.

And then there is a third group, written in a ‘let-me-explain’ style. I find them least satisfying, as I miss the presence of a central figure, whose life is opened up for the reader. The absence of such a central figure struck me most in the chapters on gender and race. I know, these are highly contested and hotly debated issues, so there is a lot to be explained to the young reader, which is helpful, but I did not come across a moment where I felt pushed to think for myself.

To the boys who turn away from a “for girls” book like this one I would say: “Come and read it; it will make you guys think more”. My verdict: highly recommended.

PS. No disappointments? Yes, two, the chapter on logic and the one of questions. The one on logic does not show the heart and power of logic. Nothing about logical puzzles and their fascination. Instead, it elaborates on the question whether there is something like ‘feminist logic’. A similar phenomenon in the chapter on questions: despite the subtitle “The heart of philosophy”, the text is only loosely and indirectly connected to the art and relevance of asking philosophical questions.

Posted by on 6th July 2021 at 12:00am

Category: Philosophy